Art is a way of expressing one’s ideas in aesthetically appealing forms. These include sculptures, paintings, masks, carvings, murals, illustrations etc. It was therefore quite natural that Srimanta Sankaradeva, the father of Assamese literature and culture used this medium to a large extent for his proselytizing activities. The Kirtanghar established by him came to be embellished with different carvings and illustrations. The manuscripts authored by him were also illustrated with pictures relevant to the stories narrated therein. And he himself initiated a new form of painting with his epoch-making drama-festival Chihna-Yatra held in 1468 A.D, where he depicted imaginary pictures of Vaikuntha or the celestial abode of God on scrolls made of pressed cotton, to be used as backdrops. Thus we can safely say that a new school of art came into being in Assam in the fifteenth century with the advent of Srimanta Sankaradeva. This school had its own characteristics, because of which we can call it the Sankari school of art form.

The religious order established by Srimanta Sankaradeva continued to sponsor this art form even after he passed away. Each residential unit maintained by his followers for proselytizing activities, which came to be known either as Than or Satra, had its own artist called Khanikar who was engaged in doing different art works like preparing masks, preparing the costumes, engraving wood panels, illustrating the manuscripts etc.1 The masks and costumes were used in the plays composed by Srimanta Sankaradeva. These were known as Ankiya plays, the enactment of which was called Bhaona. Thus it became a whole-time profession for these people, albeit as a religious work. In later days however the Khanikars became respected and well-demanded artists in the society as the Ahom kings began to patronize them. The Sankari art form has been preserved mostly by these Khanikars. They would impart training to their next generations within the precinct of and under the over-all supervision of the Than or Satra. Some Thans or Satras even maintained art schools. The Patbausi Than, originally established by Srimanta Sankaradeva, was one such Than.

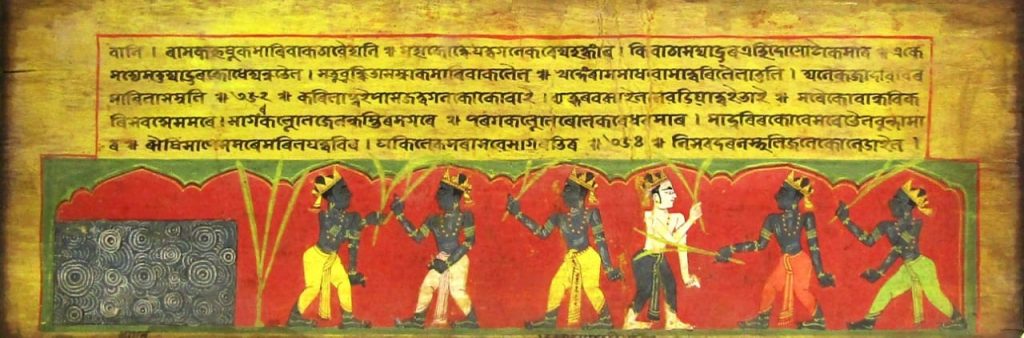

The preparation of manuscripts was itself an act of art in those days, considering the type of efforts that went into their making. Wooden pieces from the Sanchi (Aquilaria agalocha) tree were splitted, polished and treated with different reagents for a long period in order to make them fit leaves to be written upon. These leaves known as Sanchipat had great longevity and thus could be preserved for the posterity. The writing ink was prepared from Silikha (Terminalia citrina) fruit. The Sanchipat were sometimes illustrated with pictures to make them even more beautiful. The paints were prepared from vermillion, lamp-black, yellow ochre, indigo etc. It was thus that the art of manuscript painting came into being. No such painting was probably done in Assam before the time of Srimanta Sankaradeva. Regarding the painting of masks and the make-up of the actors in Bhaona (enactment of Ankiya plays), as many as twenty one ingredients were used. The most important among these were vermillion, indigo, lime and yellow ochre. The minor ingredients included mollases, yolk of the egg, the seed of the Ou fruit, the gum of the Bael (Aegle Marmelos Corr) fruit and Tamarind seeds, the juice of earthworm, charcoal of dry gourd, lamp black, sand etc.2 However these raw materials have been dispensed with in the modern times in most of the villages as different face-paints are now readily available.The Chitra-Bhagavata preserved at Bali Satra near Nagaon depicts the stories from the tenth canto of Bhagavata, which was rendered into Assamese by Srimanta Sankaradeva. This manuscript must have been prepared elsewhere and brought later to Bali Satra as this institution came into existence only in the mid-eighteenth century. According to art-historian Dr. Moti Chandra, the Chitra-Bhagavata was a work of the early eighteenth century. But the date written in the Chitra-Bhagavata happens to be 1539 AD. The figures in this manuscript have been drawn in an angular pattern and the lines are of flowing type.3 It is the earliest available illustrated manuscript of Assam. The modern art-critics consider it to be a work of the16th century. There are valid reasons to question Dr. Moti Chandra’s judgment as he used only one eighteenth century Nepali scroll to arrive at his conclusion. It is significant that the Chitra-Bhagavata costumes also resembled with the contemporary Bengal art. We have shown elsewhere how the Assamese culture was spread in that corner.4 Dr. Moti Chandra’s observation only extends the possibility of geographical spread of Assamese culture. The cause and effect relationship has unfortunately been turned upside down by these scholars. Moreover some eighth century elements are also present in this art work.5

Actually art analysis is not an absolute thing. Artist Nandalal Bose saw elements of Newari, Oriya and Jain art in Chitra-Bhagavata.6 This refutes the hypothesis of Dr. Moti Chandra. The art form laid down by the Chitra-Bhagavata of Bali Satra has guided the later day Assamese artists in manuscript illustrations. This art form was polished further in the Anadi Patan illustration found at Kuji Satra of Marigaon district, now preserved in the Assam State Museum in Guwahati, as far as abstraction is concerned. The Kuji Satra art work of Anadi Patan done on hand-made paper from cotton is an example of fine application of plastic elements. Another art work of Anadi Patan is preserved by the Kamarupa Anusandhana Samiti in Guwahati, which is done on Sanchi-bark. But it is not as fine as the Kuji Satra work. A distinctive feature of Anadi Patan art is the dependence on curves. The figures look like dolls and their eyes are wide open. The hills, rivers etc are treated in stylized manner.7 Probably the trend of abstract art started in Assam with the Anadi Patan art.

Some of the ancient pieces of Sankari art are available in the form of illustrated manuscripts preserved in different Than or Satra. The manuscript of Bhagavata with Sridhar Swami’s commentary preserved by the Korchung Satra near Nagaon is one such valuable work. The margins of this manuscript are well-illustrated. Similarly, the manuscript of Bhagavata Matsya Charita authored by Nityananda Kayastha of Mayamara Satra during 1644-50 AD and preserved at Dinjoy Satra is another instance. The wooden cover as well as the folios of this manuscript are painted with different pictures. Among them the pictures of the different incarnations of Vishnu are prominent. The manuscript of ‘Kumara-Harana’ by Ramananda Kayastha preserved at the Chaliha Bareghar Satra is also a very valuable piece of Sankari art.

Ahom kings, Rudra Singha and Siva Singha sponsored some Islamic artists brought from outside the state; the latter painted ‘Gita-Govinda’ (1695-1713 AD) and ‘Ananda Lahari’ (1720-1722 AD). Ananda Lahari had theme of Shakti cult as it was commissioned by Siva Singha’s wife, queen Pramatheswari Devi, who was a Shakti worshipper.8 This art work is depiction of Adi-Sankaracharya’s book Saundarya Lahari. Thus the royalty brought in a different school and philosophy, which partially influenced the art works sponsored by them. It cannot be said with certainty if there was a deliberate attempt to influence the Sankari school of art. While Gita-Govinda dealt with the character of Radha, the Ananda Lahari clearly ascribed to the Shakti cult as it described the deity Durga. Thus both the works were out of tune with the Sankari school. But this new development took place only after late seventeenth century, by which time the Sankari art had already got well-entrenched in the state.

Most of the Than or Satra continued with the Sankari form. Illustrations of ‘Ajamilopakhyana’ and ‘Adhyatma-Ramayana’ (1713 AD) by Vishnurama of the Chaliha Bareghar Satra was one such distinctive example. In later days occasional fusion of the royal style and the Sankari style also took place as in the case of miniature ‘Rangali-Kirtana’ (1759 AD) by an unknown artist in the court of king Rajeswara Singha. Two important works of Sankari art in the 19th century were the paintings in the ‘Parijat-Harana’ illustrations by Sasadhar Ata (1836 AD) at Aibheti-Nasatra and the illumination of ‘Brahmavaivarta Purana’ by Durgaram Betha for king Purandar Singha. It may be mentioned that king Rudra Singha also brought an Islamic painter for works like make-up of the artists. But the indigenous Khanikars maintained their Sankari style.

Apart from the above, many other manuscripts were illustrated in medieval Assam. Some of these are Lava Kushar Yuddha, Darrangi Raj Bangshawali, Banamalidevar Charita, Shangkhachura Badha, Kalki Purana, Hasti Vidyarnava, Dharma Purana, Mahabharata, Kailasha Parva, Samudra Manthana, Namghosha, Ahom Jyotish etc. The pictures of the last two manuscripts found at Sivasagar were drawn on Muga silk.

Sankari art had its own style, which was different from other art forms in the country. It was marked by the distinctive hair style, costumes, landscapes, local utensils, unique gestures, local flora and fauna, abstractness of depiction, presence of the unique symbol of winged lion, drawing of indigenous architectural pattern based on thatch-bamboo etc. The winged lion was perhaps taken from some Mangolean art brought in here by the Ahoms, who had migrated from the South East Asia. The Chitra-Bhagavata had unmaned lion and an indigenous animal ‘Methon,’ which are not seen in any other Indian art. Thus they had many local characteristics including tribal motifs.

A notable thing about Sankari art is that sometimes two events are shown together in one piece of Sanchipat itself. However the Chitra-Bhagavata was not drawn on Sanchipat, but on ‘Tulapat,’ a leaf prepared of pressed cotton. Figures are drawn within arch-typed frames in these art works. Sometime it is also a cusp. The royal art however did not use any arch. Chronological order of the pictures and presence of full details in the Sankari art underscores the importance given to the story-line than any other objective. The art was subservient to the story in the Sankari art. Colour played an important role in these art. The contrast is also very prominent here. The designs of hills and mountains are abstract; they are not present as background in the picture; the entire art used to be two-dimensional. Rain is shown by bold dotted lines. River is framed symbolically in squares with lotus, aqua leaves, fishes and geese therein. The eyes of the human characters are a little bit of the portruding type resembling with the eyes of fish. The eye-brows are carefully drawn concave downwards. The use of blue, deep red and yellow colours are pre-dominant in this art-form.

Unfortunately, we have lost most of the original staff. Only the copies of those are available now. The invaluable art objects were frequently destroyed or damaged in natural calamnities like flood and also from attack of white ants etc. So these had to be copied time and again. The apparent influence of the western schools as seen in some of the art works may have come about in the process of copying. A twentieth century copy of ‘Kirtan’ illustration found in Jorhat has all the paintings in black and the background in red. Extreme borders are made in grey in many paintings. Yellow is used for drapery, apparel and also for other purposes. Grey colour is also used for background some time. White, light blue, green etc are also used. The nudity of Saint Suka is shown without any hesitation, which was not the normal trend in Assam. Water has been shown in black here, but the Sankari art generally shows water in blue or light blue lines. However, the over-all indigenous character is retained even in the copies. For instance, Lakshmi is depicted here wearing the indigenous ‘mekhela-chadar’ while distributing nectar.

The royal art in Assam used a headgear called ‘Moglai Topi,’ which was actually an indigenous style. Such headgear is seen in a sculpture of the Mahisha demon recovered from Tinsukia. It belongs to either twelveth or thirteenth century.9 They used light green colour as background sometimes. A 18th-19th century art on ‘Syamantakamani Harana’ found at Hajo uses even black as background in the text portion. This is like the modern offset print style in reverse. So the later periods have seen lot of innovations.

Unlike art in other areas, the later day Assamese artists began to show the human bodies from front side, not in profile.10 However the Sankari art had maintained the profile form, as seen from the Chitra-Bhagavata. Royalties are shown wearing short, cone-shaped throne. The artists take their liberty in presentation of the things. An illustration in the ‘Gajendra Upakhyana’ found at Kaliabor shows the ‘Graha’ (crocodile) in the shape of a fox, thus making it a mythical concept.

Actually the Sankari art had its genesis in the epoch-making drama festival Chihna-Yatra that took place in 1468 AD. Srimanta Sankaradeva visualized and drew imaginary pictures of seven Vaikuntha on scrolls; he hung them as backdrops, when that play was staged. It was the beginning of scroll painting in entire Eastern India. Our conjecture is that the Bengal scroll painting also was derived from the Sankari school of painting. Srimanta Sankaradeva once drew an elephant for king Nara Narayana on the latter’s request.Srimanta Sankaradeva used a folk element, mask extensively in his Ankiya plays. Since then the mask has been occupying a prominent place in Assamese culture. It is a tribal heritage that probably came to Assam from the neighbouring countries like Tibbet, Bhutan, Myanmar etc. These are prepared with bamboo or wood, and then shaped with cloth and mud. Then different colours are put on it according to the character who will wear it.11 The painting of masks has already been described. The dyes used for painting the masks were prepared by the villagers themselves in the medieval period. But now-a-days the dyes are mostly procured from commercial sources since the traditional method is very laborious. It may be mentioned that the tradition of mask is still alive in Assam. It is used in the Ankiya plays.

Srimanta Sankaradeva had been groomed in a refined artistic environment; his father Kusumbar Bhuyan happened to be an expert dancer-musician. Moreover the ancient state of Kamarupa had a rich tradition in different art forms. There was a famous portrait painter named Chitralekha, who resided in Sonitpur (present Tezpur) about 3,000 years ago. She was a friend of princess Usha, who introduced the Assamese classical dance in the rest of India.12 Different tribes living here were experts in making dye.13 Ancient king Bhaskara Varmana (594-650 AD) decorated his palace with beautiful paintings, according to the Nidhanpur grant. He sent several paintings, brushes for drawing art, blank scrolls, ink etc. to his friend, king Harsha Vardhana.14

So Srimanta Sankaradeva had many ready images available before him. He did not suffer from lack of images while preparing his paintings. He undertook two extensive pilgrimages all over the country during his life-time, but both these took place long after the Chihna-Yatra. Some art-critics venture to say that the Assamese art forms were affected by the Pal art form of Bengal. But the present author has shown elsewhere that the Pal regime itself was an offshoot of an erstwhile Assamese regime and that became a means of spreading the Assamese art forms in Bengal.15 So what is known as Pal art form is nothing but an extension of the ancient Kamarupa art.

According to some critics, some motifs were taken by some Assamese artists from the North Indian schools like Jaina, Lodhi etc. The former opine that the delineation of foliage and trees is similar to some extent to the Lodhi school in some 17th and 18th century illustrations of Assam. Flame-like hills and presence of wild animals therein is another such trait, according to them. But such similarity cannot be taken as an influence. Not only that, such traits could very well have travelled from Assam to Jain, Lodhi etc schools just as Sankari dance and drama travelled to Northern India.16

Regarding the murals, we can vouchsafe that they were aplenty in the Kirtanghar constructed by Srimanta Sankaradeva and his followers. The famous Barpeta Kirtanghar is a typical example of it. The ancient hagiographies describe how this Kirtanghar was constructed with different art works and carvings on its pillars at the initiative of Madhavadeva. Unfortunately that Kirtanghar fell to fire; the subsequent restoration was made in simple manner. It is only one example of how the bamboo-thatch architecture pattern has been an obstacle in the preservation of the art works in Assam including the murals.

We see some very beautiful carvings on the altar of the prayer-house in the Sankari cult, Kirtanghar. The winged lion is carved there to represent the supreme strength of the Lord’s name to remove all demerits from one’s soul. The concept of winged lion was probably derived by Srimanta Sankaradeva from Mangolean art form as it is akin to the Chinese dragon.17 We have already shown that Srimanta Sankaradeva had folk and ethnic elements in his creative works.18 The paintings, murals and sculptures created by him also had this general characteristic.

There are also variations in the altar art in different Kirtanghar in the state. One ancient altar preserved at the Barpeta Kirtanghar shows that the altar art itself has undergone massive change over time giving a flexibility to the followers of this cult. In fact, art has been used as an instrument of philosophical analysis in the Sankari cult of Eka Sarana Nama Dharma.

The sculptures are taken as means for philosophical illumination for the devotees in this order. Some of the Kirtanghar have the dual images of the mythical characters Jay and Vijay in front of the main door to remind the devotees about the necessity of ernestness in their devotion. However no sculpture is kept inside the prayer-hall as idol-worship is prohibited in this cult. These came to be added only as paraphernalia of the Kirtanghar. For instance, sometime an image of the mythical bird ‘Garuda’ would be carved out and kept for every one to see. Such sculptures were used as visual aids for explaining religious myths and not as objects of worship. Animals or other objects were also made for use in the Ankiya plays. These were called Sanjeeva. These were made and painted just like the masks. Some popular Sanjeeva were chariots, horses, monkeys, demons, elephants, bear etc. Actually all non-human characters of the Ankiya plays were thus made in a stylized manner.19 Over time, the manuscript illustrations also found their way to the Kirtanghar buildings in the form of murals. Some of the places where art made its presence felt were the post plates, book-rests and even the ‘Sarai’ whereupon the offerings were placed. All these spread the Sankari art form all over the valley and involved the common people in it.

For Srimanta Sankaradeva, art was a quick journey from the gross to the subtle. It became clear when he once used a simple mattress Kath, designed by Madhavadeva, as metaphor to explain subtle philosophies of Bhakti Marga to the assembled devotees.20 It thus became clear that art was used by him as an aid for conveying his philosophical message.

References and notes

1. Actually Srimanta Sankaradeva had not given the name Satra to any residential unit. This name came into being for the first time in the Brahma Sanghati sub-cult after Srimanta Sankaradeva’s demise. Later it was accepted by other sub-cults of Eka Sarana Nama Dharma. But in our opinion the word Than would have been more appropriate for this Sankari institution. Now both the words are intermittently used. Asom Satra Mahasabha is also using both words.

2. Bhaonar saj-sajja aru saranjam, Jugal Das, in Sankari sangskritir adhyayan, edited by Bhavaprasad Chaliha, 2nd edition, Nagaon, 1999 AD, pp. 50-51.

3. This author has seen the Chitra-Bhagavata at Bali Satra. It is written on hand-made paper. The texture of some pieces have been slightly damaged by moisture and it badly needs modern treatment.

4. Sarvagunakara Srimanta Sankaradeva, Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 1st edition, Nagaon, 2000 AD, pp. 8-9, 24-25, 31, 33, 35-36, 45.

5. Asomor chitrakala aru satriya puthi-chitra, Jugal Das, in Bhavaprasad Chaliha, (editor), op cit, p. 128.

6. Maheswar Neogar Sankaradeva charchat pramada, Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, in Natun Dainik, edited by Dr Rohini Kumar Barua, Guwahati, May 24, 1998 AD.

7. Manuscript Paintings from Kamarupa Anusandhana Samiti, edited by Dr R. D. Choudhury & Dr N. Kalita, 1st edition, Guwahati, 2001 AD, pp. 115-116.

8. Asomor chitrakala aru satriya puthi-chitra, Jugal Das, op cit, pp. 128-129.

9. Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 1998 AD, op cit.

10.Asomor chitrakala aru satriya puthi-chitra, Jugal Das, op cit, p. 128.1

1.Bhaonar saj-sajja aru saranjam, Jugal Das, op cit, p. 47.

12.Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 2000 AD, op cit, p. 27.

13.Asom deshar buranji, Dr Lakshmi Devi, 6th edition, Guwahati, 1990 AD, pp. 87-88.

14.Ibid, p. 94; Asomor chitrakala aru satriya puthi-chitra, Jugal Das, op cit, pp. 126-127; Asomiya kristir chamu abhas, Bishnu Prasad Rabha, in Bishnu Prasad Rabha rachana sambhar, Vol II, edited by Dr Sarbeswar Bora, 1st edition, Nagaon, 1997 AD, p. 1274.

15.Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 2000 AD, op cit, pp. 24-25.

16.Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 2000 AD, op cit, p. 27.

17.Asomor chitrakala aru satriya puthi-chitra, Jugal Das, op cit, p. 128.

18.Dr Sanjib Kumar Borkakoti, 2000 AD, op cit, pp. 26-31, 34.

19.Bhaonar saj-sajja aru saranjam, Jugal Das, op cit, p. 52.

20.Katha Gurucharit, Chakrapani Vairagi, composed in about 1758 AD and collected by Dr Banikanta Kakoti, edited by Upendra Chandra Lekharu, 15th edition, Guwahati, 1987 AD, p. 132.

Earlier published in www.sankaradeva.com