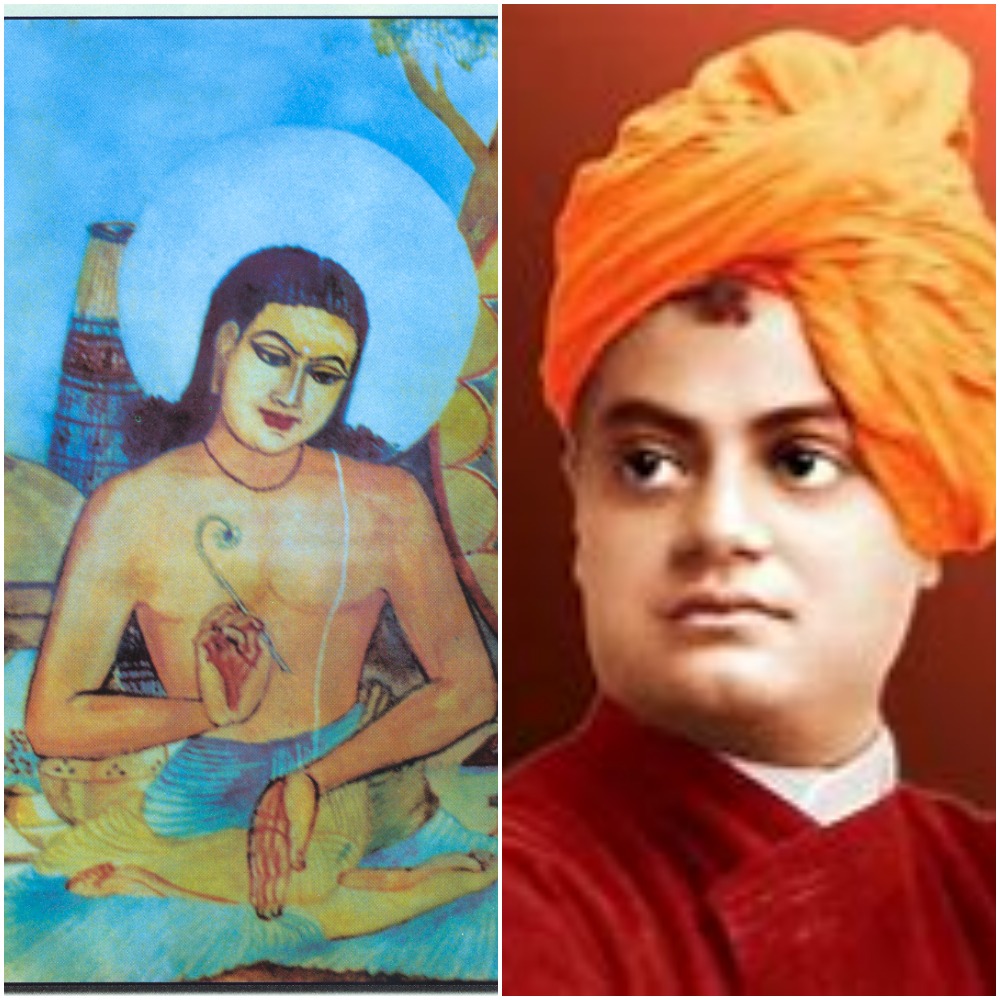

India is a great country with great cultural wealth. But her enormity also means that dimensions of all her problems also happen to be very big. Her social system has been such that from time to time it has required the service of great reformers to do away with the undesired accumulations. Srimanta Sankaradeva and Swami Vivekananda were two such great reformers who redeemed the then societies of unwarranted growths. They had different approaches to the socio-religious problems, but had many common grounds, which make interesting reading. They are two rare religious leaders who made clear statements on the Chaturbarna system and its negative impact on the Indian society. Their concerns remain valid even now, long after they have passed away from the scene.

Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902) was a fiery nationalist, who loved India and the Indians very much. He went abroad to spread the glory of India and the Indians. His profound love for the nation and her people enthused the participants of the freedom movement also greatly. He was taken as a role model by the freedom fighters. But Swami Vivekananda was not a blind supporter of everything Indian. He was very objective in his analysis and approach to any issue. He analyzed the traditions of this great country, whether ancient or medieval, very rationally and objectively. He was very ruthless in his criticism of the demerits he found in any of these traditions. But he did not criticise for the sake of criticising, as many critics tend to do. It was his rationality and objectivity that made him a modern man.

Srimanta Sankaradeva (1449-1568) was a similarly progressive religious leader who had brought about massive changes in the then society. He was a giant in Indian religious tradition. He fought the prevailing social system in Brahmaputra valley at a time when the honour of women was at stake in the hands of some Tantric priests, when education was limited to the higher castes only, when priests belonging to high castes appropriated resources from common ignorant people in the name of rituals. Srimanta Sankaradeva created a new social order where the need of the priests was done away with and no middle man was any more necessary in conducting the religious activities. He founded the Vaishnavite order Eka Sharana Nama Dharma, which preached submission and devotion to the supreme entity, lord Krishna. All devotees of that supreme entity were considered as equal entities in his order. It was a classless and casteless social order that the saint preached as well as founded. All devotees received equal treatment in his order, irrespective of whether he was a king or a beggar. He asked his disciples to treat every one, even the donor and the thief, with equal vision. [Kirtana-ghosha, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 1822] It was thus an egalitarian order.

Assam has therefore been comparatively free of the negative aspects of the Chaturbarna system, thanks to the egalitarian ideology preached by Srimanta Sankaradeva. The impact of the classless social system advocated by saint Srimanta Sankaradeva’s Vaishnavite order in the medieval era strengthened the typical Assamese social pattern. All devotees, nay all creatures are considered as equal in this order. The devotees are asked to see the almighty even in dogs, foxes, donkeys. [Kirtana-ghosha, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 1824] The predominant tribal demographic structure also prevented the discriminatory Chaturbarna system of Hinduism take firm root in Assam as the tribal societies were largely egalitarian. Srimanta Sankaradeva incorporated many ingredients from the ethnic groups in his own order. Vaishnavism preached by Srimanta Sankaradeva is thus clearly one of the factors of the liberal society of Assam. His influence extended to the societies of Northern India also together with Nanak, Kabir and Chaitanya, because he travelled extensively in Northern India for long twelve years during 1481-1493 and preached his Vaishnavism. Together, these Vaishnavite Gurus brought about a liberalism that put an end to centuries of oppression by the high caste people, especially the priests.

But the rule under the British changed many things. Many people forgot their own heritage and instead took to regressive things. It was at this juncture that Swami Vivekananda gave a clarion call to the nation to give up all demerits and reform themselves. He always tried to remind his fellow people about their great heritage, about the Vedas, the Upanishadas, the Geeta etc. He reminded them of their ancient glory and asked them to come out of the present slumber. His sole aim in life was to build India as a strong vibrant nation, albeit spiritually. But this had impact in all spheres of national life as Indian life was always permeated by spiritualism. Indian society is nothing but a spiritual approach to life. Swami Vivekananda rose to his element whenever he found spiritualism missing in any social custom. One such custom in Indian society that came under scathing attack from him was the Chaturbarna system or caste system.

The Hindus or the believers of Sanatana Dharma are the majority community in India. The Chaturbarna system was prevalent in this community since long ago. In this Chaturbarna system, people in the society are divided into four broad groups Brahmana, Kshatriya, Baishya, and Shudra. In the past, this division was made on the basis of aptitude and profession. The Brahmana were those who had aptitude for spiritualism and engaged in religious activities or teaching. By definition one who knew Brahma, the supreme absolute, became a Brahmana. So it was necessarily an area of knowledge. The Kshatriya were those who had aptitude for statecraft and engaged in administrative activities or warfare. It was the area of ruling. The Baishya were those who had aptitude for commerce and engaged in trading activities. It was the area of economic activities. All others, who served these three groups of people were known as Shudra. Clearly the Chaturbarna system was an occupational distribution. So Swami Vivekananda categorically termed it as trade guild when he referred to the Chaturbarna system of ancient period. He refused to accept it as a religious institution. He went as far as to say that caste system was only an outgrowth of the political institutions of India. [The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda (CWSV), 4th reprint, 1990, Vol 2, p. 515; Vol 5, p. 311] This criticism was made in spite of the fact that the Chaturbarna system was prescribed by the Vedas. Swami Vivekananda was well-aware of that. [CWSV, Vol 2, p. 508] This proves how modern he was. He was prepared to criticise even the holy Vedas. He went against the tradition laid down by the Vedas. He categorically declared caste as a social institution. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 198] Only a few religious leaders did that before him, that too implicitly, not explicitly.

Swami Vivekananda went to the extent of saying that the caste system was opposed to the religion of the Vedanta. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 311] It was a training school for the undeveloped mind, he said. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 305] So it was abundantly clear that he was dissatisfied with the nature and structure of the caste system and he believed that mature people should not subscribe to it. One must develop in one’s heart the feeling of the all-round good of all people irrespective of caste or colour, in order to achieve the real ideal of life, he said. [CWSV, Vol 7, p. 236] So it was clear that he considered the caste feeling as a barrier to one’s spiritual development.

Over time the castes have proliferated. There are now hundreds of castes in India, each of them restricting marriages and other social practices to among themselves. Even the educated people hesitate to marry outside one’s caste. Caste has confined the vision of social life among the people of India. This vindicates the above statement of Swami Vivekananda.

Had Chaturbarna system or caste system been a religious institution, it would have been a water-tight thing and one would not have been allowed to move across the Chaturbarna system. But there were clear movements across the castes as seen in the cases of king Vishwamitra, who changed from a Kshatriya to a Brahmana. King Harishchandra was an instance of movement from Kshatriya to Shudra. He had to give up his kingdom and become a pyre-lighter. Parashurama and Ravana, both Brahmana, were engaged in wars and administration. Therefore both upward and downward mobility in Chaturbarna system were clearly there in the ancient period. This practice of mobility continued in the period of Sankaracharya too. Swami Vivekananda discovered that Sankaracharya himself had made many Baluchi tribal people Kshatriya; the monist had also converted many fishermen to Brahmana. [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 296]

Unfortunately the occupational distribution turned into a hereditary system over time. Upward mobility of the people belonging to so-called low castes was stopped. People of so-called high castes started to look down upon people belonging to so-called low castes. An era of social discrimination started. The high castes tried to keep the power with themselves. Swami Vivekananda was very critical of Brahmana priests, who appropriated powers and priviledges to themselves. These priests managed the entire social system in such a manner that a Brahmana would not be punished even if he killed a man. A Brahmana would have to be worshipped even if he was a very wicked person. [CWSV, Vol 8, p. 95] Naturally such arrogance of the high caste people led to the growth of severe discontent in the society. This negative changes in the society brought about new discord and disorder, in place of mutual love and order of the by-gone days. The people who suffered most in the new scheme of things were the people belonging to so-called low castes. Consequently inter-caste conflicts became very common. It created enormous social tension too. Swami Vivekananda alluded to the tension between the Brahmana and the non-Brahmana in Madras Presidency. [CWSV, Vol 4, p. 299]

Swami Vivekananda was very critical of the untoward change that came about in the Chaturbarna system. He categorically said that this unwarranted change came about at the behest of the priest class only; the seers in the time of yore could not have said such things as started to be said now about the people belonging to the so-called low castes. Swami Vivekananda saw clearly that people belonging to some castes were no more equal to the people of other castes. It was the most evident in case of the Shudras. He said that the Shudras of India suffered even more than the Negroes in America.

Swami Vivekananda was a monist. But he did not hesitate to criticise the leading monists like Sankaracharya for their faith in the discriminatory attitude in the context of the Chaturbarna system. He was a vehement critic of Sankaracharya on this issue. He said, “Shankara … … was a tremendous upholder of exclusiveness as regards caste.” [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 267] It is indeed difficult to understand the contradiction in Sankaracharya, about why he was so exclusiveness as regards caste, because he was the same person who had conferred upward mobility to many people along the caste hierarchy, as mentioned earlier.

Swami Vivekananda had a message for those who were pushed down to the lowest echelon in the society because of the Chaturbarna system. He asked them to inculcate the culture and education that distinguished the people belonging to the so-called high castes. He asked non-Brahmana to acquire the culture of the Brahmana. [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 298] He also asked the Brahmana to help and elevate the non-Brahmana, that too in the spirit of servant, not a master. The Brahmana would have to give up their ego, he emphasized. They would have to prove their Brahmanahood by spirituality only, Swami Vivekananda said. He said that inter-caste quarrels would take us nowhere. [CWSV, Vol 4, p. 300] No caste could claim any right to excellence by birth, he said. He treated the “super-arrogated excellence of birth of any caste” as a myth. [CWSV, Vol 4, p. 299] Clearly he was opposed to hegemony of a single caste.

Swami Vivekananda knew well that culture and education were the two tools that transformed society. So he asked people in the lowest echelon in the society to come up on their own strength, not by dint of any force of caste, because if any upward mobility takes place due to any internal force of caste, the validity of the discriminatory Chaturbarna system will remain there. He understood that only education could bring about social change. So the priviledge of education, which was confined to the higher echelons of the society, must be made available to the lower echelons too. He said that more money should be spent in educating the people of low castes than the people of high castes, who can educate themselves without help. [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 193] The education system in our country is still not open to all, except in the lower level. The higher education, which confers competence and skill to a young person, is still available only to the priviledged class equipped with resources, as higher education has been made very costly in the new scheme of things after liberalization in the late twentieth century.

Srimanta Sankaradeva also stressed upon making education available to all people in the society. He said it categorically in his writings way back in 15th century. He wrote that interested women, Shudra and other people of low castes should be invited and given education. [Nimi nava-siddha sambada, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 333; Kirtana-ghosha, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 1827] This was a revolutionary statement. It not only asserted the rights of women, Shudra and other people of low castes to education, but also called upon rest of the society to give education to them. He asserted rights of women in his book Harishchandra Upakhyana. He gave regular discourses to his disciples about ideal way of life, even when he was travelling. He admonished them whenever any one swerved from a disciplined life style. He not only talked about spreading education, but got into action himself to materialize that. His religious institution Than, which later came to be known as Sattra, became centres of spreading education among people. His Ankiya plays containing educational materials were enacted every where in the Brahmaputra valley and beyond. These became tools for non-formal education as well as adult education. All the time he guided his people about ethical ways of life. He distributed all his books of hymns, religious plays etc among his devotees so that they could memorise the content or copy them. If we ignore the element of devotion to lord Krishna in his writings, it is all about ethics. Every chapter of his books ended with a call to people to give up bad habits and inculcate good habits. He asked people to give up demonical nature. [Kirtana-ghosha, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 359] He was clearly a great educationist who tried to elevate the society.

Swami Vivekananda wanted reform, not removal of the Chaturbarna system. He said that the caste system had benefits also, and that its benefits outweighed its disadvantages. The “caste system had grown by the practice of the son always following the business of the father….. while this divided the people, it also united them, because all the members of a caste were bound to help their fellows in case of need.” [CWSV, Vol 8, p. 242] He explained that the seers had developed this occupation-based system with good motive and it was appropriate in their time. But things changed in later period. There were a lot of new ideas put in by the priest community with vested interests. Manu, whom modern people criticise as an author of regressive mentality, could not have created a regressive system according to Swami Vivekananda. He said quoting Manu, “Learn good knowledge with all devotions from the lowest caste. Learn the way to freedom, even if it comes from a Pariah, by serving him. If a woman is a jewel, take her in marriage even if she comes from a low family of the lowest caste.” [CWSV, Vol 3, pp. 151-152]

Swami Vivekananda categorically said that the solution was “not to degrade the higher castes, not to crush out the Brahmin. … .. The solution is not by bringing down the higher, but by raising the lower up to the level of the higher.” [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 293, 295] He wanted the Brahmana to stick to their vocation as prescribed in time of yore, that was teaching of spiritualism. In his view, a Brahmana lost his claim to Brahmanahood if he engaged in non-spiritual activity. According to him “.. he is no Brahmin when he goes about making money. … … He only is the Brahmin who has no secular employment. Secular employment is not for the Brahmin but for the other castes.” [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 297] It is therefore clear that Swami Vivekananda considered many Brahmana as fallen from their caste. His support to caste system was based solely on its continuation of the ancient values laid down by the seers.

The degeneration in the Chaturbarna system was due to the attempt by a section of people to keep the priviledges confined to their own people. It was their design to prevent competition, which would have been there had inter-caste mobility continued. But the end of the mobility meant stagnation as people thereafter continued in their hereditary castes. Swami Vivekananda was highly critical of this stagnation in the Chaturbarna system. [CWSV, Vol 2, p. 516] He praised Buddha highly for attacking the caste system. He was a great admirer of Buddha who “fought the degenerated castes with their hereditary priviledges.” [CWSV, Vol 2, p. 508] But he had a different approach than Buddha for doing away with the priviledges of the high castes. While Buddha followed the path of renunctiation, Swami Vivekananda prescribed the path of action, Karma Yoga. He said that materialism came to the rescue of India by way of opening the doors of life to every one and destroying the exclusive priviledges enjoyed by the people of high castes. [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 157] It was an interesting approach to the problems of the country, more so coming from a monk. But it spoke volume about his pragmatic approach. He termed caste distinction as gateway to hell and insisted that such distinction must be dispensed with in the places of pilgrimage. One who looked at caste of people could not love God, he said. [CWSV, Vol 6, p. 369] Caste was the greatest dividing factor and the root of Maya, he said. Caste was bondage, he declared emphatically. [CWSV, Vol 6, p. 394] So it is evident that his analysis was spiritual.

When we compare Swami Vivekananda’s view with that of Srimanta Sankaradeva, we find many similarities in their views and activities. Both were highly educated and great travellers. Both tried to reform their contemporary societies. This is specially true in case of their perspectives on Chaturbarna system. Both the reformers were very fond of Jagannath temple in Puri, in the precinct of which there was no caste discrimination and all devotees were treated as equal. [CWSV, Vol 7, p. 294] Srimanta Sankaradeva stayed for months at a stretch in Puri whenever he visited this temple. He also created a casteless society wherever he went. The egalitarian Atibari cult of Odisha was formed under his direct influence. Swami Vivekananda also said that social conditions had to be changed in order to abolish caste. [CWSV, Vol 2, p. 516] He was also sure that such a change was happening. There were increased competition in the modern world, because of which caste was fast disappearing. People were increasingly taking up professions outside their traditional caste activities. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 23] But nevertheless Swami Vivekananda did not ask for outright rejection of the Chaturbarna system. In fact he was proud of his Kshatriya legacy as this caste had “ruled half of India for centuries” and he said emphatically that nothing would be left of “present civilization of India” if his caste was left out of consideration. [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 211]

Swami Vivekananda criticised the degenerate form of caste, not its original form. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 198] So he was not at all apologetic about the heritage, but at the same time he was conscious about its demerits. He categorically said that the modern caste distinctions happened to be barriers to India’s progress. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 198] What mattered was reaching the lower castes. He lamented that social reforms like widow remarriage did not touch the lower castes having “seventy percent of the Indian women” and such issues reached only the “first two castes.” [CWSV, Vol 3, p. 216] Such concerns for the so-called low castes clearly unite Srimanta Sankaradeva and Swami Vivekananda. Quite interestingly both belonged to the same Kayastha caste by birth, and both transcended caste. Srimanta Sankaradeva engaged Radhika, a lady from fishermen caste as leader of the volunteers who constructed a river dam at his native place Bardowa near Nagaon under his supervision. Devotees from all castes sat together in his place, in the worshipping hall Kirtanghar, a practice continued till today.

The situation in Assam had always been a little different from elsewhere in India. The negative aspect of the Chaturbarna system was not prominent here. The demographic pattern of Assam was the secret behind that. Assam has always been full of ethnic groups. There were several tribes living here since long ago and there were migrations of other tribes from across the borders over the centuries. All these tribes maintained community lives in egalitarian pattern. Over time most of these tribes adopted Sanatana Dharma or Hinduism. There were only upward mobility within the caste system here, no downward mobility. The ethnic groups were incorporated into the caste system on their accepting Hinduism and awarded a higher place in the society compared to before; but still they had been kept at the bottom on the social scale. So the hiatus was still there, although less than in the rest of India. The scenario changed with the advent of Srimanta Sankaradeva whose Vaishnavite order ‘Eka Sarana Nama Dharma’ gave equal status to all. He did away with all hierarchical divisions, all hiatus. He categorically said that devotion did not take into account the caste of the devotee; one need not take birth as Brahmana; the only requirement was that one should chant the name of lord Hari. [Kirtana-ghosha, Srimanta Sankaradeva, verse 129] The upward mobility in his egalitarian order made the order immensely popular. In fact this is a common feature of most of the Vaishnavite orders, who have thereby succeeded in bringing people under a common flag. This impact of Vaishnavism was appreciated openly and unhesitatingly by Swami Vivekananda, even though he did not mention the name of Srimanta Sankaradeva, may be due to his non-acquaintance with the activities of the saint. [CWSV, Vol 5, p. 234]

Regarding continuation of caste, we have found that people at large are fed up with caste hierarchy and have gradually discarded it. Inter-caste marriages are now common place. Actually Chaturbarna system or caste system is being kept alive by the present day governments as they give different facilities to people on the basis of caste. They have even started making census survey on the basis of caste. They gather data about caste from government employees too. Earlier there was only one caste system in India. But now there are two types of caste systems : the socio-religious caste system known as Chaturbarna system and the government-sponsored caste system. The political parties of India are using caste as a tool for their electoral gains, which has resulted in increasing discord and disorder than ever before. While the principle of elevating the lower castes by offering incentives in education and services is welcome from welfare principle, use of this principle with political motive has distorted the entire scenario and created mutual distrust and conflicts. The decision to conduct the census of population on the basis of castes since 2012 has given the final stamp of approval on the continuity of caste system and thereby strengthened the distorted version of the Chaturbarna system.

Acknowledgement :

This article was earlier published in the website www.sankaradeva.com